The modern sneaker is a deceptive object. It sits quietly in a hallway or a gym locker, appearing to be a simple assembly of rubber, foam, and fabric. Yet, underneath the laces and logos lies a feat of complex engineering that rivals the automotive industry in its precision.

Sneaker manufacturing is where performance engineering collides with high fashion. It is a process that has evolved radically over the last century. We have moved from the simple, vulcanized rubber plimsolls of the early 1900s to the hyper-technical, 3D-printed, carbon-plated footwear of today.

Understanding how a sneaker is made requires peeling back the layers—literally. It is not merely about stitching pieces together; it is about chemistry, biomechanics, and industrial design. This guide explores the entire production journey, detailing the specific machinery, manual craftsmanship, and technological innovations that transform raw pellets of plastic and rolls of mesh into the shoes on your feet.

See also: Evolution of Shoes

See also: How Shoes Are Designed From Scratch

Step 1: Sneaker Design and Concept Development

Before a single piece of leather is cut or a mold is cast, the sneaker exists as a problem to be solved. The design phase is often romanticized as a sketch on a napkin, but in modern manufacturing, it is a rigorous process of market analysis and architectural planning.

Trend Research and Inspiration

The lifecycle begins with the “brief.” Product managers and designers collaborate to determine the shoe’s purpose. Is it a marathon runner requiring maximum energy return? A lifestyle silhouette aimed at urban commuters? Or a basketball shoe that needs to support 250 pounds of force?

Designers act as historians and futurists simultaneously. They analyze archival silhouettes to ground the shoe in heritage while forecasting color and material trends two years in advance. They create “mood boards”—collages of textures, architectural shapes, and color palettes—to establish the aesthetic direction.

Sketching and Digital Modeling

Once the concept is approved, the visualization begins. While hand-sketching remains the quickest way to iterate ideas, the industry has largely migrated to 3D CAD (Computer-Aided Design) software.

Tools like Rhino, Modo, or specialized footwear software allow designers to build the shoe in a virtual environment. They can test different colorways, adjust the thickness of the midsole, and even simulate how materials will wrinkle or fold, all without building a physical sample. This digital twin accelerates the process, allowing factories to understand the exact specifications of the “upper” (the top part of the shoe) and the “tooling” (the bottom sole unit).

Silhouette Planning

The silhouette is the outline of the shoe—its shadow. It is the most defining characteristic of a sneaker. During the design phase, the profile is rigorously debated. A low-profile silhouette suggests speed and agility (think vintage track spikes), while a chunky, high-profile silhouette communicates durability and stability (think 90s basketball shoes).

See also: Shoe Silhouettes Explained

Step 2: Material Selection for Sneakers

A sneaker is only as good as its ingredients. Unlike dress shoes, which rely heavily on different grades of leather, sneakers utilize a vast library of synthetic and natural materials designed for specific performance metrics.

Mesh and Knit Uppers

In the last decade, the industry has shifted away from multi-panel construction toward single-piece knit or mesh uppers.

- Engineered Mesh: This is a woven synthetic, usually polyester or nylon, with varying degrees of openness. Tighter weaves provide support, while open weaves offer breathability. It is lightweight and cheap to produce.

- Circular Knit (Flyknit/Primeknit): This technology uses computer-controlled knitting machines to weave the entire upper as a single sock-like tube. It drastically reduces waste because there are no off-cuts, and it allows designers to change the elasticity of the fabric in specific zones without adding seams.

Synthetic Overlays

To provide structure to these soft mesh uppers, manufacturers use overlays. Historically, these were suede or leather patches stitched on. Today, they are often Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU).

TPU is a class of plastic that can be melted and bonded to the shoe. It creates a “skeleton” for the sneaker, locking the foot in place during lateral movements. It is lighter than leather and offers a futuristic, seamless aesthetic.

Cushioning Foam Materials

The “midsole”—the layer between your foot and the ground—is the engine of the sneaker. The selection of foam here dictates the ride.

- EVA (Ethylene Vinyl Acetate): The standard white foam seen on most sneakers. It is light and cushions well but compresses over time (“bottoms out”).

- PU (Polyurethane): A denser, heavier foam often used in retro sneakers or hiking boots. It is durable but less bouncy.

- eTPU (Expanded TPU): Popularized by Adidas Boost technology, this involves fusing thousands of energy capsules together. It provides higher energy return than standard EVA.

See also: Leather vs Synthetic Shoe Materials

See also: Sustainable Shoe Materials Guide

Step 3: Upper Construction and Stitching

Once materials are chosen, the physical assembly begins. This takes place in the “stitching” or “closing” room of the factory. Despite automation, this stage remains incredibly labor-intensive and relies heavily on human dexterity.

Panel Assembly

The raw materials arrive in large rolls or hides. They are sent to the “Clicking” department. Here, hydraulic presses use metal dies (like cookie cutters) to punch out the specific shapes needed for the shoe. For limited runs or complex prototypes, computer-controlled laser cutters are used for precision.

These flat pieces are then organized into kits. A standard retro sneaker might have 20 to 30 separate components that need to be assembled like a complex 3D puzzle.

Heat Bonding vs. Stitching

Traditionally, these panels were sewn together by hundreds of workers operating heavy-duty sewing machines. Stitching is durable and offers a classic look, but it adds weight and friction points that can cause blisters.

Modern manufacturing favors “No-Sew” or “Heat Bonding” methods. Panels of TPU are placed over the mesh, and the assembly is run through a heat press. The heat activates the adhesive backing on the TPU, fusing the layers together instantly. This creates a lighter, sleeker shoe with better aerodynamic properties.

Branding Elements

Logos are rarely just printed on. They are usually structural. The famous “swoosh” or “stripes” on the side of a sneaker often serve as a saddle, connecting the laces to the sole unit to tighten the fit around the midfoot. These elements are applied during the upper assembly, ensuring the branding is integral to the shoe’s function, not just its decoration.

See also: Shoe Stitching Techniques Explained

Step 4: Lasting and Shaping the Sneaker

This is the most critical moment in shoe manufacturing. “Lasting” is the process where the flat, 2D upper is pulled over a 3D foot form called a “Last.”

Stretching Upper Over the Last

The Last is a mold, usually made of high-density plastic, that mimics the human foot. Every shoe size and width requires its own specific Last.

The stitched upper is heated in a steam tunnel to make the materials pliable. It is then placed over the Last. A machine grips the bottom edge of the upper and pulls it down tight against the bottom of the Last with immense pressure.

This process imparts the three-dimensional shape to the shoe. If the lasting is too loose, the shoe will be sloppy and unsupportive. If it is too tight, the materials may tear or the fit will be restrictive.

Securing Structure

There are two main ways to secure the upper during lasting, which drastically affects how the finished sneaker feels:

- Strobel Lasting: This is the industry standard for athletic sneakers. The bottom edge of the upper is stitched to a soft fabric sheet (the Strobel board) like a sock. It is flexible and allows the cushioning of the midsole to be felt immediately.

- Board Lasting: The upper is glued to a stiff cardboard or plastic board. This is common in hiking boots or dress shoes where rigidity and stability are prioritized over flexibility.

See also: Lasting Process in Shoemaking

Step 5: Midsole and Outsole Assembly

While the upper is being stitched, a separate part of the factory—the “Stock Fitting” room—is preparing the bottom of the shoe.

Cushioning Technologies

The midsole is typically created through injection molding. Pellets of foam (EVA or specialized compounds) are injected into a steel mold. Heat and pressure cause the foam to expand and fill the cavity, capturing every detail of the design, from compression grooves to logos.

If the sneaker uses an “Air” unit or gel pocket, these components are inserted into the mold before the foam is injected, encapsulating them within the midsole.

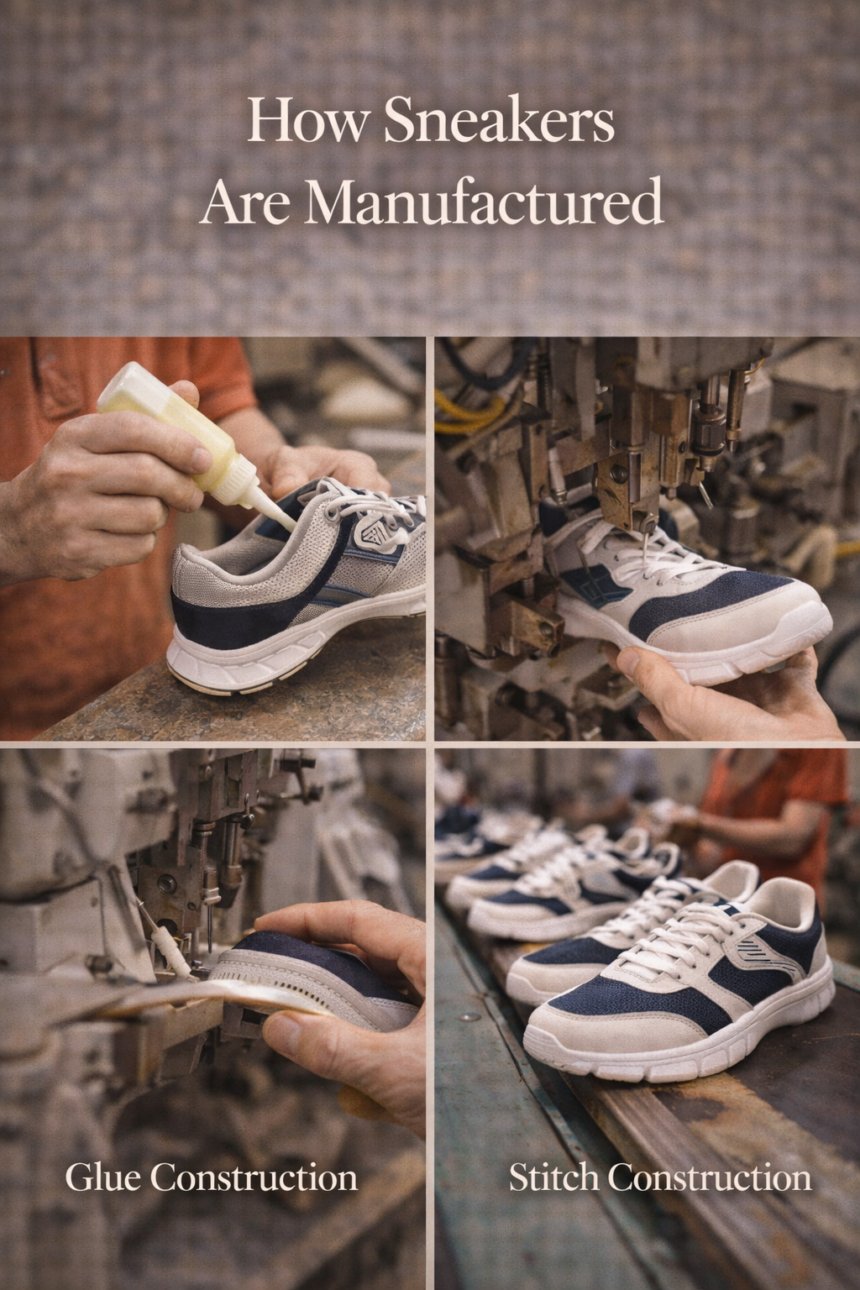

Glue vs. Stitch Construction

The marriage of the upper and the sole is called “bottoming.”

- Cold Cement: The most common method for sneakers. Both the lasted upper and the sole unit are coated in primer and cement. They pass through a heat tunnel to activate the glue, are pressed together by a hydraulic machine, and then pass through a cooling tunnel to set the bond.

- Cupsole Stitching: For skate shoes or retro basketball sneakers, the rubber sole sits up around the edge of the upper (like a cup). It is often stitched through the rubber and into the upper for mechanical durability, ensuring the sole never peels off.

Traction Patterns

The final layer is the outsole—the rubber skin that touches the ground. The tread pattern is engineered based on the sport. Herringbone patterns are used for basketball to allow multi-directional pivots. Waffle patterns are used for running to provide forward grip. The rubber is vulcanized or cured to ensure it is tough enough to withstand abrasion against concrete.

See also: Cushioning Technologies Explained

See also: Glue vs Stitch Construction

Step 6: Finishing, Testing and Packaging

The shoe is physically complete, but it is not yet a product ready for retail.

Quality Control

Every pair goes through a rigorous inspection. Workers trim loose threads, clean off excess glue (often using UV light to spot invisible primer stains), and ensure the left and right shoes are symmetrical.

Comfort Testing

Random samples are pulled from the line for destruction testing. They are put into machines that flex the sole 30,000 times to check for cracking, or abrasion machines that rub the fabric until it fails. If a batch fails these tests, the entire production run is halted.

Final Presentation

The Last is finally removed from the shoe. A sockliner (insole) is inserted for immediate step-in comfort. The shoes are laced, stuffed with tissue paper to hold their shape, and placed into the box. This packaging is the first physical touchpoint for the customer, bridging the gap between the factory floor and the consumer’s closet.

See also: Step-by-Step Shoe Manufacturing Process

How Manufacturing Shapes Sneaker Silhouettes

It is easy to think that designers dictate trends, but often, it is the manufacturing capabilities that dictate the design.

Chunky Sneaker Trends

The “Dad Shoe” or chunky sneaker trend was largely enabled by advancements in injection molding. Manufacturers figured out how to create massive, oversized midsoles that were still lightweight by injecting air into the foam compounds. Twenty years ago, a midsole that size would have been like wearing concrete blocks.

Minimalist Performance Designs

Conversely, the “sock shoe” silhouette (like the Balenciaga Speed Trainer or Nike Free) exists only because of circular knitting machines. Before this technology, creating a supportive shoe without internal stiffeners and heavy leather panels was impossible. Manufacturing innovation allowed for a deconstructed aesthetic that changed street style.

See also: Classic Sneaker Silhouettes That Changed Fashion History

The Future of Sneaker Manufacturing

The sneaker industry is currently undergoing its biggest shift since the invention of the assembly line.

Automation and Robotics

Brands are moving toward “Speedfactories.” These are highly automated facilities located closer to the consumer (in Europe or the US) rather than in Asia. Robots are beginning to handle the complex tasks of lasting and cementing, reducing the reliance on manual labor and speeding up the time from design to shelf.

AI-Driven Design

Generative design is entering the space. Designers can input parameters—”I need a sole that supports a 200lb runner with a heel strike”—and AI algorithms generate complex, lattice-structured soles that no human could draw. These are then 3D printed, creating performance capabilities tailored to individual biometrics.

Sustainable Production Methods

The future is circular. Manufacturing is moving away from glues, which make shoes hard to recycle. New prototypes allow shoes to be locked together mechanically or made of a single material (TPU) so the entire shoe can be ground down and remelted into a new shoe at the end of its life.

See also: The Future of Shoes: Technology & Innovation

Conclusion: Technology Meets Craft in Modern Sneakers

The journey of a sneaker from a digital file to a finished product is a testament to human ingenuity. It is a process that balances the brute force of hydraulic presses with the delicate touch of hand-stitching.

As we look at the shoes on our feet, we are looking at the culmination of a global supply chain, advanced chemical engineering, and artistic vision. Whether it is a mass-market running shoe or a limited-edition luxury sneaker, the manufacturing process is the backbone of sneaker culture. It defines not just how the shoe performs, but how it looks, how long it lasts, and ultimately, how it moves us forward.

See also: How Shoes Are Made: Complete Guide

Leave a Reply