If you were to dissect the anatomy of a shoe, peeling back the layers of leather, foam, and rubber, you would eventually find yourself staring at a void. That negative space inside the footwear isn’t accidental; it is the ghost of the most critical tool in the shoemaker’s arsenal: the last.

The “lasting” process is the bridge between a two-dimensional design and a three-dimensional object. It is the moment when flat pieces of material—leather, canvas, synthetic mesh—are stretched, pulled, and coerced into a wearable form. Without lasting, a shoe is merely a collection of parts. With lasting, it becomes a vessel for the human foot, capable of movement, protection, and style.

In the grand timeline of human evolution, the development of the last represents a significant leap in cognitive design. It signifies the moment we stopped wrapping hides arbitrarily around our feet and started engineering footwear that mimicked and supported our biology. Today, whether in a bespoke atelier in London or a high-volume factory in Vietnam, the lasting process remains the heartbeat of shoe manufacturing.

This guide explores the technical, historical, and artistic nuances of lasting, revealing how this invisible process dictates the comfort, silhouette, and soul of every shoe you wear.

Read Here: How Shoes Are Made

What Is Lasting in Shoemaking?

At its simplest, “lasting” is the mechanical or manual process of pulling the shoe upper (the part that covers the foot) over a “last” (a mold that simulates the foot) and securing it to the bottom of the shoe, usually an insole or board.

The last itself is the alpha and omega of footwear design. Historically carved from hardwoods like maple or beech, and now primarily made from high-density polyethylene plastic, the last determines the internal volume, width, arch height, and toe shape of the final product. It is a proxy for the human foot, but it is not an exact replica. A last must account for movement, the expansion of the foot during walking, and the specific aesthetic the designer aims to achieve.

The Role of Tension and Memory

Lasting is not just about covering a mold; it is about tension. Materials like leather have a grain and a stretch direction. When a shoemaker pulls the leather over the last, they are creating tension that locks the shape into the material’s “memory.”

Once the upper is secured to the bottom board, it is often left on the last for a period—ranging from a few minutes in mass production to several weeks in bespoke shoemaking—to ensure the material settles permanently into that shape. If the lasting is done poorly, the shoe will lose its form after a few wears, sagging and gaping in unsightly ways. If done correctly, the shoe will hold its silhouette for years, supporting the wearer through millions of steps.

For a deeper dive into the components being manipulated during this phase, refer to our guide on Parts of a Shoe Explained.

The Purpose of the Shoe Last

The last is often described as the soul of the shoe. While the outsole provides traction and the upper provides style, the last provides the character. It dictates three fundamental pillars of footwear: shape, fit, and structure.

Shape and Proportion

Fashion historians can date a shoe simply by looking at the toe box. The square toes of the 1990s, the pointed winklepickers of the 1950s, and the bulbous clown-toe profiles of contemporary maximalist sneakers are all results of the last.

Designers use the last to manipulate the visual weight of a shoe. A “fast” last might have a sleek, aerodynamic taper, used for racing flats or dress shoes. A “high-volume” last might look blocky and utilitarian, suitable for work boots. The last allows the designer to control the proportion of the shoe in relation to the leg, influencing the entire silhouette.

Fit and Ergonomics

This is where the science of biomechanics enters the craft. A shoe must fit a dynamic, moving object. The foot elongates when it bears weight and spreads at the metatarsals. A well-engineered last accounts for this. It includes “allowances”—extra millimeters added to the length and width—to ensure the toes aren’t crushed during the push-off phase of walking.

The “cone” of the last (the top part corresponding to the instep) dictates how tight the shoe feels across the top of the foot. If the cone is too high, the foot slides forward; too low, and it cuts off circulation.

Structural Support

Finally, the last provides the rigid surface against which the shoe is constructed. You cannot hammer a nail or press a cemented sole onto a soft, empty bag of leather. The last acts as an anvil. It provides the resistance needed to attach the sole unit securely, ensuring the structural integrity of the footwear.

To understand how the initial concept translates to this physical form, read How Shoes Are Designed From Scratch.

Main Types of Lasting Methods

Not all shoes are lasted equally. The method chosen depends on the intended use of the shoe—whether it needs to be rigid and supportive for hiking, or flexible and lightweight for running.

Strobel Lasting

If you look inside your running shoes or sneakers, you will likely see a line of stitching running around the perimeter of the insole, connecting a fabric bottom to the upper. This is Strobel lasting.

Named after the specific machine used to sew the fabric, this method creates a sock-like pouch. The upper and bottom material are stitched together before the last is inserted. Once sewn, the last is forced inside to give it shape.

- Pros: Extremely flexible, lightweight, and cost-effective.

- Cons: Offers less structural rigidity and stability compared to board lasting.

Board Lasting

This is the traditional method used for dress shoes, boots, and hiking footwear. The upper is pulled over the last and secured to a rigid insole board using glue, staples, or tacks.

- Pros: Provides excellent stability and support. The shoe holds its shape firmly.

- Cons: Can be stiff and heavy. Requires a “break-in” period for the wearer.

Slip Lasting

Common in moccasins and very lightweight casual shoes, slip lasting involves constructing the shoe without a rigid insole board. The upper material wraps completely around the foot and is sewn together, often down the center of the sole.

- Pros: Maximum flexibility and a “glove-like” fit.

- Cons: Very little arch support or protection from the ground.

Combination Lasting

As the name implies, this method combines techniques. A shoe might be board-lasted in the heel for stability and Strobel-lasted in the forefoot for flexibility. This is common in high-performance basketball and tennis shoes.

For a broader look at assembly techniques, see Shoe Stitching Techniques Explained.

Step-by-Step Lasting Process

While automation has sped up the process, the fundamental physics of lasting remain the same. Here is how a flat piece of material becomes a shoe.

1. Preparing the Upper and Insole

Before lasting begins, the “closed” upper (all stitching complete, eyelets installed) is heated. Heating makes materials like leather and thermoplastics pliable. Meanwhile, the insole board is temporarily tacked or attached to the bottom of the last.

2. Pulling Over (Drafting)

This is the critical moment. The upper is placed over the last. In a factory setting, a machine with pincers grabs the edge of the leather at the toe. It pulls the material forward and down, stretching it tightly over the “feather edge” (the bottom edge) of the last.

The goal is to remove all wrinkles without tearing the material. The tension must be balanced; pull too hard on the right, and the tongue of the shoe will twist to the left.

3. Side and Heel Lasting

Once the toe is secured, the sides (waist) and heel are pulled down. The material is wrapped tightly under the insole board. In modern manufacturing, this is done by a machine that injects hot-melt adhesive and wipes the material flat against the board in a single motion.

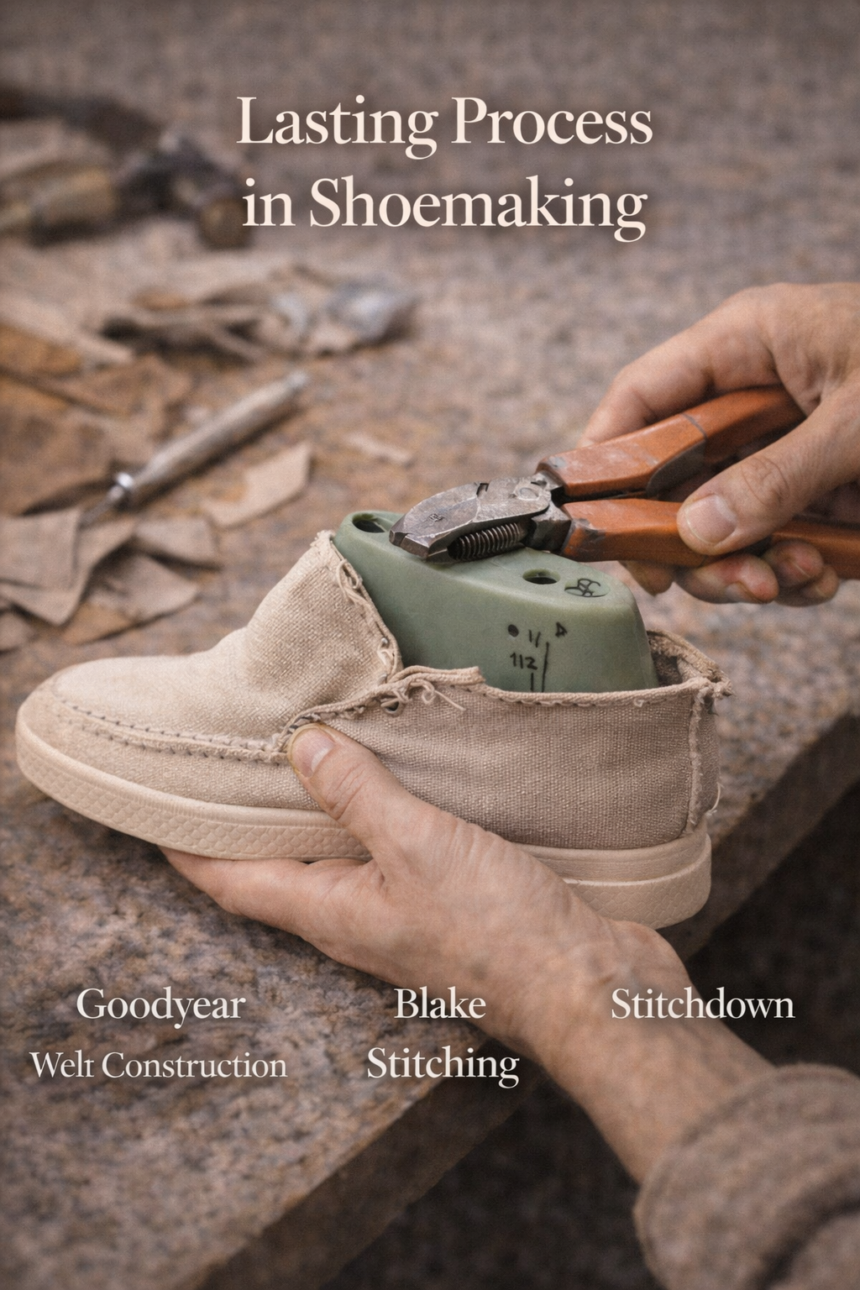

In traditional shoemaking, this is done with a pair of lasting pliers, a hammer, and nails. The shoemaker pulls the leather, drives a nail, and hammers it flat, moving inch by inch around the shoe.

4. Heat Setting and Conditioning

Once the shoe is fully lasted, it is often passed through a heat tunnel or left on a rack. This “shocks” the material into its new shape. The fibers of the leather or synthetic mesh relax into the new configuration, ensuring the shoe doesn’t spring back to its flat state once the last is removed.

5. Roughing and Sole Attachment

The excess material gathered at the bottom is trimmed (skived) to be flat. The surface is then “roughed” or sanded to create a texture that glue can adhere to. Finally, the outsole is attached.

For a complete overview of the assembly line, visit our Step-by-Step Shoe Manufacturing Process.

How Lasting Shapes Shoe Silhouettes

The lasting process is the primary driver of a shoe’s visual identity. It is where the “vibe” of the shoe is solidified.

High-Top vs. Low-Top Structure

While the pattern cut determines the height of the collar, lasting determines how that collar sits against the ankle. A “straight” last will result in a boot shaft that stands upright (like a cowboy boot), while a curved last creates a silhouette that hugs the Achilles tendon (like a modern running shoe).

Chunky vs. Minimalist Forms

The volume of the last dictates the bulk of the shoe. A minimalist sneaker, like a Common Projects Achilles, uses a low-profile last with very little excess volume. The leather is pulled extremely tight, creating a sleek, aerodynamic look. Conversely, a “chunky” sneaker (think Balenciaga Triple S) uses a high-volume last with padded linings. The lasting process here is about managing bulk, ensuring the layers of foam and mesh bulge outward in a controlled, deliberate manner.

Athletic vs. Formal Profiles

Athletic lasts typically feature a high “toe spring”—the upward curve of the sole at the toes. This promotes a rolling motion during running. The lasting process must lock this curve in place. Formal shoes usually have a flatter profile and a sharper “feather edge” (the corner where the side meets the sole), creating a crisp, defined line that implies elegance and rigidity.

To explore how these shapes have evolved over decades, explore Shoe Silhouettes Explained.

Handmade vs. Factory Lasting Techniques

The divide between bespoke craftsmanship and mass production is perhaps most visible in the lasting room.

Artisan Craftsmanship: The Hand Laster

In high-end bespoke shoemaking (think Savile Row or Italian bottegas), lasting is a physical wrestling match. The cordwainer uses lasting pliers—a tool unchanged for centuries—to leverage the leather over the wood.

They rely on tactile feedback. They can feel the grain of the leather stretching. If a section feels loose, they pull harder. If the leather is stiff, they wet it and hammer it gently. This allows for micro-adjustments that machines cannot replicate. A hand-lasted shoe carries the tension perfectly distributed by human judgment.

Industrial Automation: The Machine Laster

In a factory producing 10,000 pairs a day, consistency is king. Automated lasting machines use hydraulic pincers to pull the upper. These machines are incredibly precise, ensuring that the left shoe is mathematically identical to the right shoe.

However, machines lack feeling. If a piece of leather has a scar or a soft spot, the machine treats it the same as a pristine piece, which can occasionally lead to defects or uneven stretching.

To understand the value differences between these methods, read Handmade Shoes vs Factory Shoes.

Modern Innovations in Lasting Technology

We are currently in a transition period in footwear history. While the principle of lasting hasn’t changed, the technology surrounding it is accelerating.

Digital Fit Scanning and Custom Lasts

The “holy grail” of modern footwear is mass customization. Brands are beginning to use 3D scanners to map a customer’s foot in retail stores. This data can be used to mill a custom last (or select the nearest perfect match from a digital library). This marks a return to the bespoke ideology—shoes made for your feet—but executed at industrial speed.

Automated Knitting and 3D Printing

Technologies like Nike Flyknit or Adidas Primeknit have changed lasting. Because the upper is knitted into a specific 3D shape, the lasting process is less about stretching and forcing, and more about setting.

Furthermore, 3D printing is challenging the need for lasts entirely. Some experimental footwear is printed as a complete, single unit. If the shoe is printed in 3D space, does it need to be lasted? This question is currently reshaping the industry.

Sustainable Construction Methods

Traditional lasting relies heavily on solvent-based glues to hold the upper to the insole board. These glues are often toxic and difficult to recycle. New innovations in “thermal lasting” use heat-activated yarns that fuse together, eliminating the need for chemical adhesives. This makes the shoe easier to disassemble and recycle at the end of its life.

For more on where the industry is heading, see The Future of Shoes: Technology & Innovation.

Conclusion: Lasting as the Core of Shoe Construction

Lasting is the unsung hero of the footwear world. It is a process that happens behind closed factory doors, obscured by linings and outsoles. Yet, it is the single most important factor in how a shoe feels when you lace it up in the morning.

It is the discipline where physics meets artistry. It transforms a flat, lifeless pattern into a dynamic, three-dimensional object capable of protecting the human foot as it traverses the world. Whether it is the soft, unstructured hug of a moccasin or the rigid, protective shell of a work boot, the character of the shoe is defined in the lasting room.

As we look toward a future of 3D printing and smart materials, the tools may change, but the goal remains the same: to shape material to the complex, beautiful, and demanding anatomy of the human foot.

For a broader view of the entire production journey, visit our authority hub: How Shoes Are Made: Complete Guide.

Leave a Reply