Every time you take a step, the integrity of your footwear is put to the test. Whether you are walking in a pair of high-end dress shoes, rugged boots, or lightweight running sneakers, the bond between the upper (the part that covers your foot) and the sole (what hits the ground) is the most critical structural component.

For most consumers, this connection is invisible. We look at the leather quality, the silhouette, or the brand logo. However, the method used to attach these two distinct parts—either through industrial adhesives or traditional stitching—dictates the shoe’s lifespan, water resistance, flexibility, and repairability.

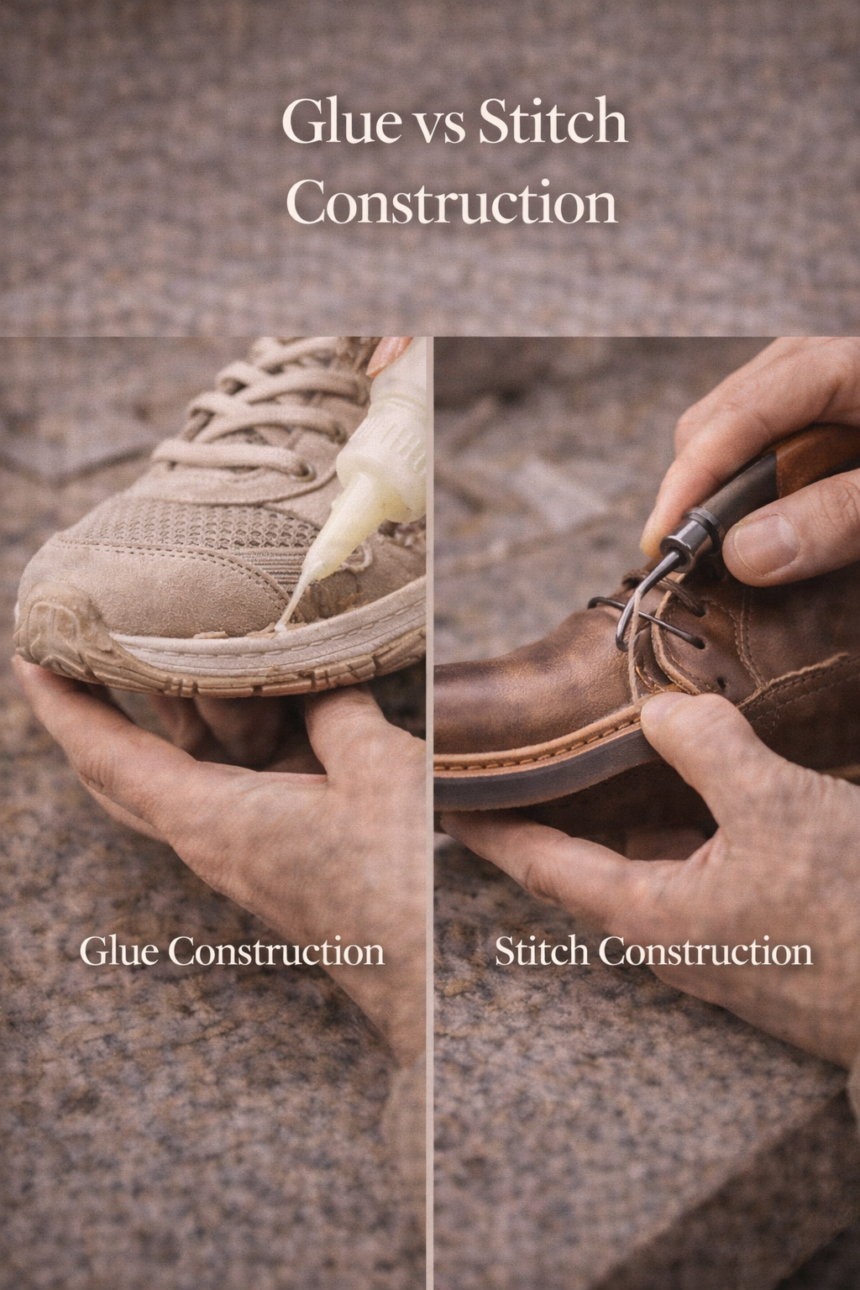

In the world of shoemaking, this debate is often framed as “Glue vs. Stitch.” It represents a clash between modern efficiency and heritage craftsmanship, between lightweight performance and rugged longevity. Understanding these methods isn’t just academic; it helps you make smarter purchasing decisions and appreciate the engineering beneath your feet.

Introduction: Why Shoe Construction Methods Matter

The way a shoe is put together is often more important than the materials used. You could have the finest Italian calfskin upper, but if it is attached to the sole with a weak adhesive that degrades in humidity, the shoe is effectively useless within a year. Conversely, a synthetic sneaker built with advanced bonding techniques can withstand marathon-level stress.

Historically, shoemaking was a purely mechanical process. Before the 20th century, if you wanted two pieces of leather to stay together, you sewed them. The evolution of chemical engineering brought us cements and glues, revolutionizing the industry by allowing for mass production, lower costs, and entirely new designs that needles and thread simply couldn’t achieve.

For the modern buyer, knowing the difference between a cemented (glued) shoe and a stitched (welted or blake) shoe is the difference between buying a disposable commodity and investing in a long-term wardrobe staple. It explains why a pair of boots might cost $500 while a visually similar pair costs $50.

See also: [Evolution of Shoes]

See also: [Parts of a Shoe Explained]

What Is Glue (Cemented) Shoe Construction?

Cemented construction, often referred to as “gluing,” is the most common method of shoe manufacturing today. It is the standard for sneakers, casual shoes, and a vast majority of fast-fashion footwear. In this process, the upper is shaped around a last (the mold that mimics a foot), and the outsole is attached using a powerful adhesive. No welt or stitching is used to hold the sole to the upper.

How Adhesive Bonding Works

The process is deceptive in its simplicity but requires precise chemical conditions to work. The bottom of the upper material is usually roughened or “buffed” to create a texture that the glue can grip. A primer is often applied, followed by a layer of heat-activated cement (usually polyurethane or neoprene-based) on both the upper and the outsole.

The two pieces are then heated to activate the adhesive and pressed together under high pressure. This creates an immediate, watertight bond. In modern manufacturing, this process is highly automated, allowing factories to produce thousands of pairs per day with consistent results.

Advantages of Cemented Construction

The primary benefit of cemented construction is cost and speed. Because it eliminates several labor-intensive steps found in stitching, these shoes are cheaper to produce and, consequently, cheaper to buy.

However, it isn’t just about cost cutting. Cementing allows for a sleek, close-cut aesthetic. Without the need for a bulky welt (the strip of leather used in stitching), the sole can sit flush against the upper, creating a streamlined look popular in fashion sneakers and light dress shoes.

Furthermore, cemented shoes are significantly lighter and more flexible right out of the box. There is no rigorous “break-in” period required, as there are no stiff leather welts or heavy stitching to soften up. This makes them ideal for athletic footwear where flexibility and weight reduction are paramount.

Limitations of Glue-Based Methods

The major drawback of cemented shoes is longevity. Over time, the chemical bonds in the glue can break down, especially when exposed to heat or moisture. This leads to “sole separation,” where the sole literally flaps off the shoe.

Perhaps the most significant disadvantage is that cemented shoes are generally considered disposable. Once the sole wears out or detaches, they are difficult—often impossible—to resole. A cobbler cannot simply stitch a new sole on; the old glue must be stripped, which often damages the upper material. For this reason, cemented shoes are rarely seen as lifetime investments.

See also: [Step-by-Step Shoe Manufacturing Process]

What Is Stitch Construction?

Stitched construction relies on physical interlocking mechanisms—thread and needle—to hold the shoe together. This is the traditional method, favored by heritage brands and high-end shoemakers. While there are many variations, the principle remains the same: a mechanical bond that can be undone and redone.

Blake Stitching

Blake stitching is a method popularized in Italy. It involves a single stitch that runs from the inside of the shoe, through the insole, through the upper, and directly into the outsole.

Because there are no intermediate layers or exterior welts, Blake-stitched shoes can be cut very close to the foot, offering a sleek, elegant profile similar to cemented shoes but with the security of stitching. They are also more flexible than other stitched methods. The downside is that because the stitching goes through to the inside of the shoe, water can wick up through the holes, making them less water-resistant.

Goodyear Welt Construction

The gold standard for durability is the Goodyear Welt. Developed in the late 1800s, this method uses an indirect attachment. A strip of leather (the welt) is stitched to the upper and the insole. Then, a separate stitch attaches the welt to the outsole.

The magic of this system is that the outsole is not directly stitched to the upper. If the sole wears out, a cobbler can cut the stitches connecting the sole to the welt and attach a new one without ever touching the upper leather. This allows Goodyear-welted boots to last for decades, often going through three, four, or five sole replacements. They are, however, stiffer, heavier, and more expensive to produce.

Strobel Stitching

Common in athletic shoes, Strobel stitching is a hybrid technique. The upper material is stitched to a flexible fabric bottom (the Strobel board) to create a sock-like pouch. The outsole is then cemented to this unit. While it technically uses stitching, it functions more like a cemented shoe in terms of repairability, but offers incredible flexibility and comfort for running and movement.

See also: [Shoe Stitching Techniques Explained]

Glue vs Stitch: Key Differences

When deciding between these two schools of thought, it helps to break down the differences into practical categories.

Durability and Longevity

Stitching wins on longevity. A physical thread lock is less susceptible to environmental degradation than chemical adhesives. While modern glues are strong, they eventually dry out, crack, or peel. A stitched shoe, particularly a Goodyear welt, maintains its structural integrity for years. However, high-quality cemented hiking boots can still offer excellent durability for their specific lifespan, even if they aren’t “heirlooms.”

Comfort and Flexibility

Cemented and Strobel-stitched shoes generally win on immediate comfort. They are flexible and soft from the first wear. Stitched footwear, especially welted construction, requires a break-in period. The layers of leather, cork filling, and heavy thread need time to mold to the wearer’s foot and soften at flex points. However, once broken in, a high-quality stitched shoe offers superior support.

Cost and Accessibility

Glue construction dominates the mass market because it is affordable. You can find cemented shoes at every price point, from $20 discount store sneakers to $200 designer flats. Stitched construction requires skilled labor and specialized machinery, pushing the price point higher. You will rarely find a genuine Goodyear welted shoe for under $150, and prices often soar into the thousands for bespoke options.

Repairability

This is the defining difference. Stitched shoes are designed to be serviced. A $400 pair of boots can be resoled for $80, effectively giving you a “new” shoe. Cemented shoes are designed to be replaced. When the sole dies, the shoe dies. From an environmental standpoint, stitched footwear promotes a culture of repair rather than a culture of disposal.

See also: [Complete Guide to Types of Shoes]

How Construction Methods Influence Shoe Silhouettes

The way a shoe is built dictates how it looks. The construction method acts as a constraint or an enabler for the designer, influencing the volume, the edge, and the profile of the final product.

Chunky Sole Designs

Current fashion trends favoring chunky, “dad shoe” aesthetics or platform boots often utilize cemented or molded construction. To achieve massive, oversized sole units, manufacturers often use injection molding where the sole is bonded directly to the upper. Stitching through three inches of rubber is impractical, so glue becomes the architect of these voluminous shapes.

Minimalist Lightweight Shoes

For a shoe to look “barely there,” such as a delicate ballet flat or a low-profile driving loafer, the construction must be unobtrusive. Cementing allows the upper to roll under the foot and attach to a thin sole without a protruding edge. Blake stitching also allows for this, but cementing is the only way to achieve the ultra-thin, flexible soles found in minimalist footwear.

Formal vs Athletic Profiles

The sharp, defined edge of a dress shoe is often a result of the welt. That little ridge of leather sticking out around the toe of an Oxford is the tell-tale sign of stitch construction, signaling formality and tradition. Conversely, the seamless transition between the knit upper and foam sole of a running shoe signals athleticism and aerodynamics—a look only achievable through modern bonding and Strobel methods.

See also: [Shoe Silhouettes Explained]

Handmade Craftsmanship vs Modern Factory Production

The debate between glue and stitch is also a conversation about the soul of manufacturing.

Stitch construction, particularly when done by hand (Hand Welted), is an art form. It requires a craftsman to use an awl and bristle to weave threads through tough leather. Even machine-assisted Goodyear welting requires a skilled operator to guide the shoe. This human element introduces slight variations that give the shoe character. It is a slow, deliberate process.

Cemented construction is the triumph of industrial engineering. It is fast, precise, and highly automated. Robots can apply primer and glue with millimeter accuracy, and hydraulic presses ensure a bond strength that human hands couldn’t replicate consistently. While it lacks the romance of the artisan’s workshop, it democratizes footwear, making decent shoes accessible to the global population.

However, we are seeing a shift. Some high-end sneaker brands are now introducing stitching to their cupsoles (the rubber cup that holds the foot) to simulate quality, even if the primary bond is still glue. Conversely, some traditional shoemakers are using modern adhesives to reinforce their stitching, creating hybrid durability.

See also: [Handmade Shoes vs Factory Shoes]

The Future of Shoe Construction Technology

We are currently in a transition period where the lines between these methods are blurring.

Advanced Bonding Materials

The “glue” of the future is not the glue of the past. Companies are developing bio-based adhesives that are stronger than traditional petrochemical glues but biodegradable. We are also seeing the rise of “direct attach” construction, where the sole material is injected in liquid form directly onto the upper, fusing them together at a molecular level without traditional glue or stitching. This creates an inseparable bond that is waterproof and incredibly durable.

Hybrid Stitch-Glue Systems

Designers are beginning to mix methods for optimal performance. You might see a boot with a stitched forefoot for flexibility and a cemented heel for stability. Or, manufacturers might use a “storm welt”—a stitch construction designed to be waterproof—reinforced with modern sealants to ensure no moisture penetrates the needle holes.

Sustainable Adhesives

As the fashion industry faces scrutiny for its environmental impact, the toxicity of shoe glues is a major hurdle. The future lies in water-based, non-toxic cements that provide the strength of industrial glue without the harmful VOCs (Volatile Organic Compounds), making the factory floor safer for workers and the shoes safer for the planet.

See also: [The Future of Shoes: Technology & Innovation]

Choosing the Right Construction for Your Needs

So, which is better? The answer depends entirely on what you need the shoe to do.

If you are a long-distance runner, a basketball player, or someone looking for an affordable, lightweight fashion statement, cemented (glue) construction is the superior choice. It offers the performance and price point that fits that lifestyle.

If you are looking for a pair of dress shoes for the office, rugged boots for work, or simply want to invest in a product that will age with you and can be repaired over the decades, stitch construction is the only way to go.

The best shoe collection likely contains both. The key is understanding what you are paying for so you don’t end up with a glued shoe at a stitched price, or a heavy welted boot when you really needed a flexible sneaker.

See also: [How Shoes Are Made: Complete Guide]

Leave a Reply