When we look at a shoe, we often see the whole—the silhouette, the brand logo, or the colorway. But a shoe is a sophisticated feat of engineering, a sum of many intricate parts working in unison to provide protection, stability, style, and cultural signaling. Whether it’s a Goodyear-welted Oxford or a high-performance running sneaker, the anatomy of footwear tells the story of human innovation.

Understanding the components of a shoe shifts your perspective from seeing footwear as a mere accessory to appreciating it as a constructed object. It allows you to make better purchasing decisions, understand fit and comfort on a deeper level, and recognize quality craftsmanship when you see it.

This guide breaks down the complex architecture of footwear. As part of our Complete Human Shoes Evolution Project, we explore how these individual elements have evolved from primitive foot coverings to the technologically advanced designs of today.

Why Shoe Anatomy Matters

For most people, a shoe is simply a tool for walking. But for designers, podiatrists, and historians, a shoe is a map of human needs. Every stitch, panel, and material choice serves a specific function rooted in biomechanics or cultural expression.

The anatomy of a shoe dictates its lifespan. A cemented sole might last a season, while a stitched construction can last a decade. The anatomy dictates comfort; the choice of EVA foam versus polyurethane in a midsole changes energy return entirely. And finally, anatomy dictates silhouette—the visual profile that defines trends and eras.

By understanding these parts, you unlock the language of footwear. You begin to see why a chukka boot feels different than a Chelsea boot, not just because of how they look, but because of how they are built.

The Three Main Sections of a Shoe

At its most fundamental level, every shoe can be divided into three primary zones. These three layers form the “sandwich” that protects the human foot from the ground.

The Upper

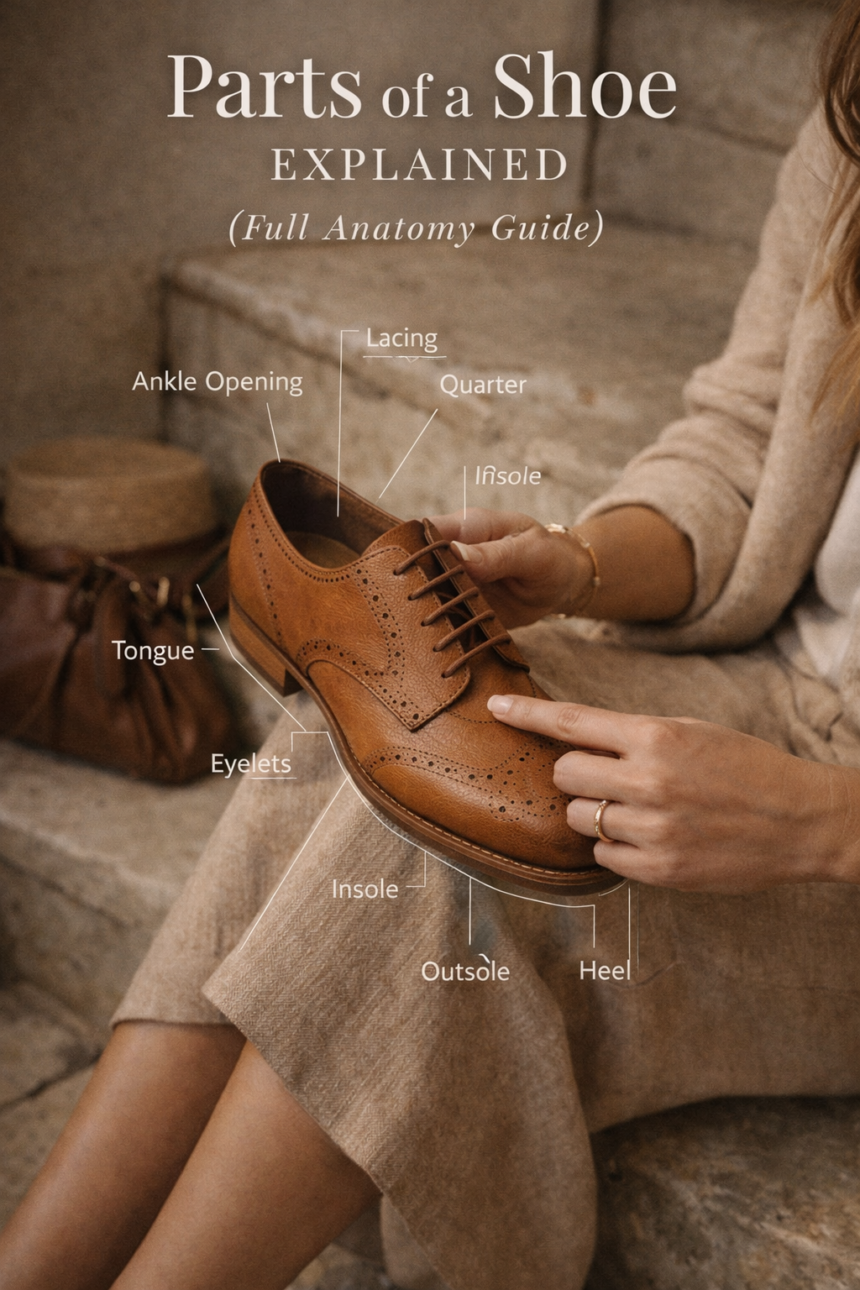

The upper is the part of the shoe that covers the top, sides, and back of the foot. It is the visual identity of the shoe—the canvas for design, color, and texture. Historically made from leather or canvas, modern uppers utilize complex knit technologies and synthetic meshes. Its primary job is to hold the foot securely to the sole while offering breathability and protection.

The Midsole

Located between the upper and the outsole, the midsole is the engine of the shoe. This is where the magic of cushioning and stability happens. In modern athletic footwear, the midsole is the focus of intense technological warfare, with brands developing proprietary foams and plates to maximize energy return. In traditional formal footwear, the midsole may be a simple layer of cork or leather designed to mold to the foot over time.

The Outsole

The outsole is the bottom-most layer that makes direct contact with the ground. It is responsible for traction, durability, and protection against the elements. From the aggressive lugs of a hiking boot to the smooth leather sole of a dress shoe, the outsole defines the shoe’s intended terrain.

Upper Components Explained

The upper is rarely a single piece of material. It is a complex assembly of panels, creating the structure that wraps around the foot.

The Toe Box

The toe box covers and protects the toes. Its shape is a critical factor in both comfort and style. A pointed toe box (common in winklepickers or stilettos) elongates the leg but restricts toe splay. A wide, rounded toe box (seen in work boots or barefoot shoes) prioritizes comfort and natural foot mechanics. The evolution of the toe box often mirrors the prevailing aesthetic of the decade—square in the 90s, pointed in the 2000s, and increasingly anatomical today.

The Vamp

Moving backward from the toe box, the vamp covers the top of the foot (the instep). In many shoe designs, this is the largest continuous piece of material. The vamp creates the primary flex point of the shoe. Because it creases every time you take a step, high-quality material selection here is crucial to prevent cracking or unsightly wear patterns.

The Quarter Panel

The quarter panel wraps around the sides and back of the foot, meeting the vamp. In athletic shoes, this area often houses the branding (like the Nike Swoosh or Adidas stripes) and provides lateral stability. In dress shoes, the distinction between the vamp and the quarter often defines the style—for example, in an Oxford shoe, the quarter is stitched under the vamp (closed lacing), whereas in a Derby, it is stitched over the vamp (open lacing).

The Heel Counter

Hidden between the lining and the outer material at the back of the shoe is the heel counter. This is a stiff insert (usually plastic or firm leather) that cups the heel. Its function is vital: it locks the foot in place, preventing slippage and providing structural integrity. If you have ever stepped on the back of your shoe and crushed it, you have damaged the heel counter. A strong counter is often a sign of a high-quality shoe.

The Tongue & Collar

The tongue sits under the laces, protecting the top of the foot from the pressure of the binding system. It is often padded for comfort. The collar is the rim of the shoe that encircles the ankle. In performance footwear, the collar is heavily padded to prevent chafing and secure the ankle joint, while in minimalist designs, it may be a raw edge for a sleek silhouette.

Sole Construction Breakdown

While the upper provides the style, the sole unit provides the function. This is where engineering meets the pavement.

Midsole Technologies

The midsole is the heart of modern comfort.

- EVA (Ethylene Vinyl Acetate): The industry standard for decades. It is lightweight, cheap, and offers decent cushioning, though it compresses over time.

- PU (Polyurethane): Denser and heavier than EVA, but far more durable. Common in hiking boots and high-end sneakers.

- Modern Foams: Brands now use proprietary chemistry (like Adidas Boost or Nike ZoomX) to create materials that don’t just cushion impact but return energy to the wearer, propelling them forward.

- Cork: In traditional welted footwear, a layer of cork paste is often used. It is not bouncy like foam, but it creates a custom footbed as it molds to the wearer’s footprint over months of wear.

Outsole Patterns

The tread pattern on the bottom of a shoe is not random; it is physics in action.

- Waffle/Lug: Deep grooves designed to dig into soft surfaces like mud or dirt.

- Herringbone: A zig-zag pattern famous in basketball shoes for allowing multi-directional traction on hard courts.

- Smooth/Leather: Designed to reduce friction, allowing for pivoting (in dancing) or simply providing a sleek profile for formal occasions.

The Heel Stack

In formal footwear, the heel is often a separate unit attached to the sole. A “stacked heel” consists of layers of leather or wood glued and nailed together. This elevates the wearer and alters posture. In athletic shoes, the “heel drop” (the height difference between the heel and toe) is a critical spec—sprinters prefer a high drop for forward momentum, while minimalists prefer a “zero drop” to mimic being barefoot.

Fastening Systems and Structural Details

How a shoe attaches to the foot changes its category entirely. The fastening system is a blend of mechanics and aesthetics.

Laces (The Aglet and Eyelet)

The most common securing method. Laces thread through eyelets (the holes). Eyelets may be punched directly into leather, reinforced with metal grommets for durability, or created using fabric loops (gillies). The plastic or metal tip at the end of a shoelace is called an aglet. While small, the aglet prevents fraying and makes threading the laces possible.

Velcro (Hook and Loop)

Introduced in the mid-20th century, Velcro changed accessibility. It allowed for rapid fastening and became associated with both toddler shoes (for ease of use) and geriatric footwear. However, high-fashion streetwear has reclaimed Velcro straps as a brutalist design element.

Slip-On Construction (Gores)

Shoes without fasteners rely on elastic panels called gores. These stretch to allow the foot to enter and then snap back to secure the fit. The Chelsea boot is the most famous example of this engineering, proving that a shoe can be secure without a single lace.

Stitching, Lasting & Internal Structure

You cannot see the most important parts of a shoe. The internal assembly—how the upper is attached to the sole—is the true mark of quality.

The Last

Every shoe begins with a Last. This is a 3D mold (plastic or wood) that simulates the human foot. The upper is stretched over the last to give the shoe its shape. The “lasting” process defines the volume, width, and toe shape. A shoe made on a poorly designed last will never fit comfortably, regardless of the materials used.

Strobel Construction

If you pull out the insole of your running shoe, you will likely see stitching around the perimeter. This is Strobel construction. The upper is sewn to a fabric bottom sheet (like a sock) and then glued to the midsole. It is lightweight and extremely flexible, making it ideal for sneakers.

Board Lasting

Here, the upper is glued to a stiff fiberboard. This makes the shoe stable and rigid but less flexible. This is common in hiking boots or cheaper dress shoes where support is prioritized over flexibility.

Cemented vs. Stitched (Welted)

- Cemented: The upper is simply glued to the sole. It is cheap, fast, and waterproof, but once the glue fails, the shoe is dead. Most sneakers use this method.

- Blake Stitch: The upper is stitched directly through the insole to the outsole. It creates a sleek, flexible dress shoe, but water can wick through the stitches.

- Goodyear Welt: The gold standard for durability. A strip of leather (the welt) is stitched to the upper and insole, and then the outsole is stitched to the welt. It is waterproof and, crucially, allows a cobbler to replace the sole repeatedly.

How Shoe Anatomy Shapes Silhouettes

The anatomy of a shoe is what creates the “silhouette”—the outline or profile of the footwear. This is where engineering meets art.

- Chunky vs. Minimal: The volume of the midsole dictates the visual weight. The “Dad Shoe” trend relied on over-engineered, thick midsoles to create a heavy, grounded silhouette. Conversely, a ballet flat removes the midsole almost entirely for a delicate, barely-there profile.

- The Throat: The opening of the shoe where the foot enters is called the throat. A deep throat (cut low toward the toes) elongates the leg line. A high throat (like a high-top sneaker or boot) shortens the leg line but adds visual mass to the ankle.

- Toe Spring: Put a running shoe on a flat table. You will notice the toe curls upward, not touching the surface. This is toe spring. It is engineered to help the foot roll through a step. Anatomically, it aids movement, but visually, it gives the shoe a sense of speed and dynamism even when standing still.

Cultural and Functional Meaning of Shoe Design

Why do we design shoes the way we do? The evolution of shoe anatomy tracks the evolution of human culture.

The High Heel

Originally designed for Persian cavalrymen to keep their feet in stirrups, the heel became a status symbol in the French courts (red heels for nobility). Over centuries, it shifted from a masculine tool of war to a feminine symbol of grace and restriction. The anatomy here—elevating the calcaneus bone—drastically alters the wearer’s posture, forcing the chest out and the hips to sway.

The Air Bubble

In the late 1980s, Nike exposed the internal anatomy of the midsole with the Air Max. Suddenly, technology wasn’t just felt; it was seen. This shifted sneaker culture from purely functional to deeply aesthetic. The visible technology signaled that the wearer was on the cutting edge of modernity.

The Red Sole

Christian Louboutin painted the outsole of a shoe red, transforming the most utilitarian, dirty part of the shoe into its most valuable asset. It turned anatomy on its head, proving that even the part of the shoe that touches the pavement can be a status signal.

The Future of Shoe Anatomy

As we look toward the future of footwear, the anatomy of the shoe is undergoing a radical transformation driven by sustainability and AI.

- 3D Printed Structures: We are moving away from gluing layers of foam together. Future midsoles are being 3D printed in lattice structures (like Adidas 4D). This allows designers to tune the cushioning at a micro-level—making the heel stiff and the toe soft within a single continuous material.

- Bio-Materials: The uppers of the future are being grown, not woven. Mushroom leather (mycelium) and lab-grown textiles are replacing cowhide and plastic. This changes the anatomy of production, moving from extraction to cultivation.

- The End of the Glue: One of the biggest hurdles in shoe recycling is separating the upper from the sole. New designs aim for “circular anatomy,” where the shoe is constructed from a single material or can be easily disassembled, allowing for true recycling.

Understanding Shoes Beyond the Surface

When you understand the anatomy of a shoe, you stop looking at footwear as disposable fashion and start seeing it as functional art. You recognize that the Heel Counter is keeping you stable, the Goodyear Welt is an investment in longevity, and the Toe Spring is propelling you forward.

This guide serves as the foundation for your journey into footwear. Now that you know the parts, you are ready to explore how they come together to form the icons of history.

Take the next step in your education by exploring our guide on Shoe Silhouettes Explained, where we apply this anatomical knowledge to the most famous designs in history.

The Complete Guide to Types of Shoes: Styles, Structure & Purpose

Leave a Reply